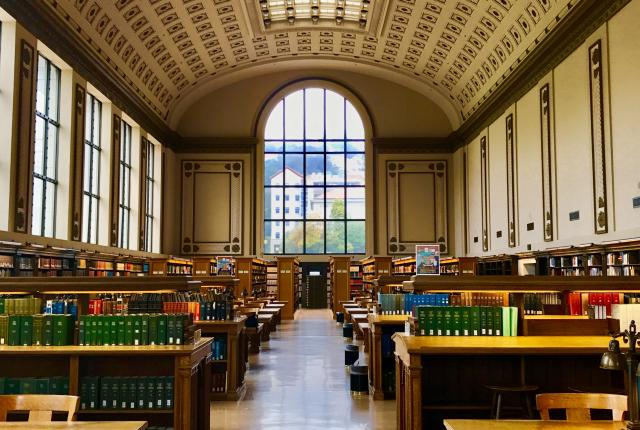

“…The more that you read, the more things you will know. The more that you learn, the more places you’ll go….”

– Dr. Seuss –

2025

SPRING 2025 EDITION

Authors: Mansa Devaki, Maia Hernandez, Caitlin Hong, Melbourne Romney, Sidd Sen

Editors: Nathan Hahn, Ben Segev

Up to Fall 2024

ARCHIVE

Explore our curated collection of insightful blogs from the past in the Archive, where we dive into diverse topics ranging from debunking premed myths to health research. Each post is crafted to inform, inspire, and engage readers with thought-provoking ideas and in-depth perspectives. Whether you’re revisiting past articles or discovering new insights, our archive serves as a rich repository of knowledge and stories that continue to resonate.

Stay informed. Stay inspired.