Debunking Premed Myths

Written by: Gautam Naik | Edited by: Arshad Mohammed

In order to debunk common pre med myths, I spoke with Mr. Hugo Mora-Torres, who is currently a pre med counselor at UC Berkeley. His knowledge regarding medical schools and their expectations comes from extensive training through the National Association of Advisors for Health Professionals (NAAHP), from weekly newsletters containing information from deans and admission committees of institutions, and from experience. Ultimately, the wealth of his knowledge is fact-based and not opinion-based.

- Being at a premier research institution, many premed students believe that they must be involved in research from their early years in order to be competitive during the medical school application process. What are your thoughts on this?

This is not true at all. While many students do pursue research while at Berkeley, it is in no way required as medical schools use a holistic review system during the application process. A model regarding the holistic review process can be found at the end of this Q&A along with a brief explanation of its different parts. Ultimately though, while research is in no capacity required to be competitive for medical school, it can serve as a great way to build various Attributes and Experiences. Through research, your critical thinking skills can grow and improve along with developing your quantitative reasoning, scientific inquiry, and written communication skills. Therefore, it does serve as a great way to grow as a student and to form relationships with professors and graduate students, which can be helpful for LORs during the application process.

- Often, premed students work hard to attain a flawless ‘A’ transcript, often sacrificing parts of their social life or mental health to do so, believing that all med students have such grades and that they are needed to be competitive. They believe that even one bad grade ruins your shot at medical school. Is this true?

Similar to my answer to #1, there is simply a baseline for GPAs and MCAT Scores. Once these thresholds are met, your Attributes and Experiences are considered. These aspects beyond grades help to determine if one has the capacity to be a good doctor. While grades show that one is intelligent, dedicated, and committed, it does not serve as an indicator or a guarantee that you will be a good doctor. As a result, your Attributes and Experiences are a big part of the process for admissions committees. While grades are not an end all be all, we should all have high academic standards in order to give us the best possible shot at medical school.

- In a bid to strengthen our resume and build medical experience, premed students can often sacrifice their other passions and hobbies, because they feel like it may not be valued by medical schools, like volunteering and clinical experience are the only things that matter. What is your opinion on this?

This is not the case at all. As long as your other hobbies and interests do not distract you from your medical ambitions, they are definitely important as an investment in activities shows commitment. This can help strengthen your attributes while simultaneously building great experiences that you can speak to during your application.

- Medical schools prefer premed applicants pursuing a science major (i.e. MCB, IB, MEB) over those pursuing a non-science major, because it shows they are more ‘committed’. Do med schools actually have a preference?

Medical schools do not have any preference whatsoever. Most premed students simply choose to pursue a science major like MCB or IB because many of their major requirements align with the prerequisites of medical schools.

- To be competitive for medical school, you have to spend your summers at a prestigious summer program or research institution. Simply volunteering or working at a clinic or other non profit organization is not enough. Is this the case?

Not necessarily. In your application, you must speak to the quality of the program and the impact it has had on you. Certain research programs do get funded by the NIH, so you might have richer experiences there. However, it must be a good fit. You can only have a quality experience that impacts you if you participate in a program or larger organization that aligns with your interests and provides great mentorship. More than worrying about how prestigious your summer program/activity may be, it is more important to first begin with a positive mindset geared towards learning and wanting to be challenged. This will allow you to utilize every opportunity given to you and build a rich summer experience. Finally, the richer the experience, the stronger an LOR your mentor will be able to write for you.

- For medical school, all you have to do is meet a certain level of participation in activities like volunteering or clinical experience. Once a certain amount of hours are performed, this will help your case for medical school, acting almost like a checklist.

Similar to #5, what matters is quality, not quantity. These activities aren’t just checkboxes on a form. They are experiences that help us grow into students and people that have the potential to be great doctors. During these experiences, a positive mindset, strong work-ethic, and extensive self-reflection is crucial to grow such that you become better prepared for medical school. Ultimately, more than just checkboxes, volunteering and clinical work are experiences geared towards helping us grow as students and as people to help us become more capable doctors.

- Medical schools view more ‘challenging’ majors as an advantage and will view poorer grades with more leniency. Is this true?

Not at all. Medical schools make no such differentiation. They view all grades the same despite your major, because the major you should be taking is the one that genuinely interests you. Therefore, medical schools show no sort of preference or increased leniency for ‘challenging’ majors, and, thus, challenging majors do not excuse poor grades.

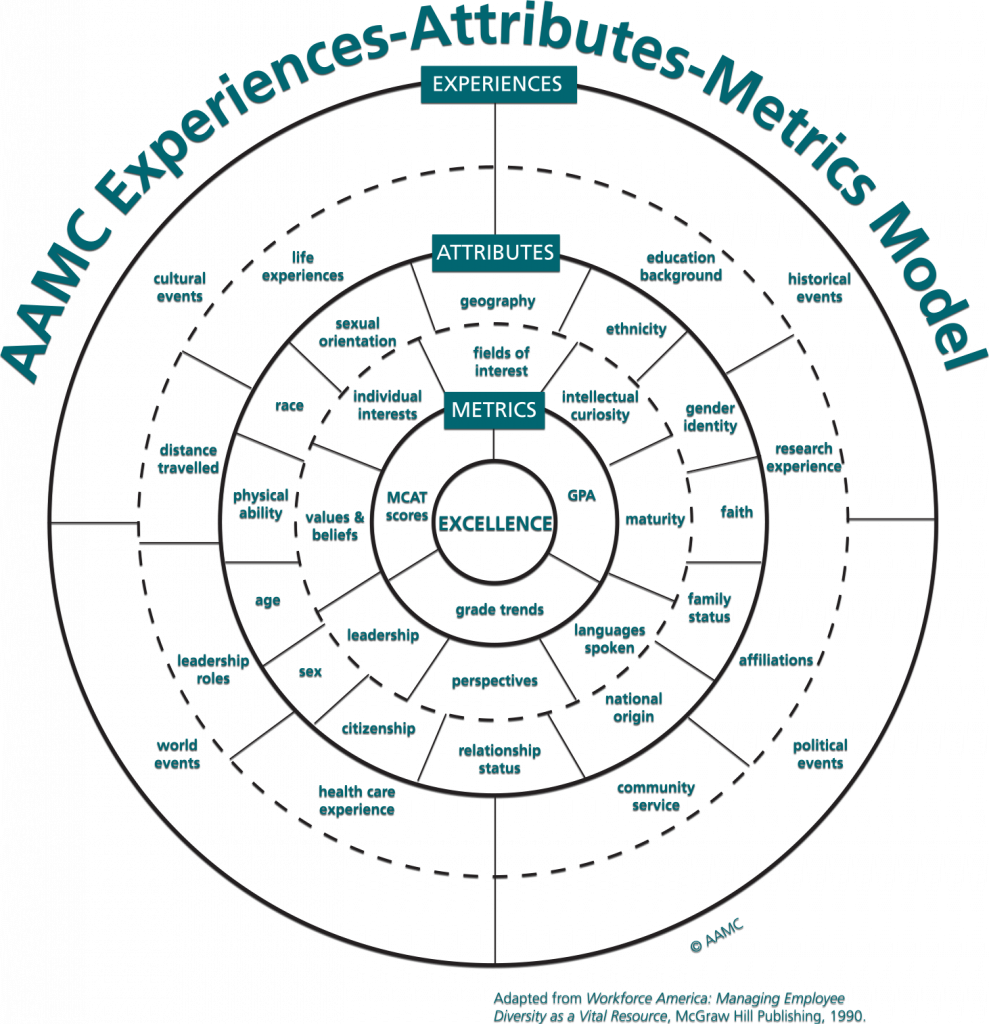

The above model represents the holistic review process used by medical school admissions committees. In this model, there are three distinct parts: Metrics, Attributes, and Experiences

- Metrics→ These serve as a baseline. Once the minimum is met, the other two categories are considered.

- Attributes→ Primarily includes skills, personality, and traits. Considers how you have grown as a student and as a person throughout college and what you have gained.

- Experiences→ Considers general life experiences, including your time volunteering, doing clinical work, and conducting research (if applicable)